Ridwan Oloyede

Introduction

In an increasingly digital world, Automated Decision-Making (ADM) systems are rapidly changing how we interact with individuals, businesses and governments. From loan approvals and online behavioural advertisement to recruitment processes, algorithms are now making decisions that significantly impact individuals’ lives. While ADM systems offer efficiency and scalability, they also raise concerns about fairness, transparency, and potential bias. This article explores how African data protection laws approach this complex issue, highlighting the commonalities and divergences in their provisions.

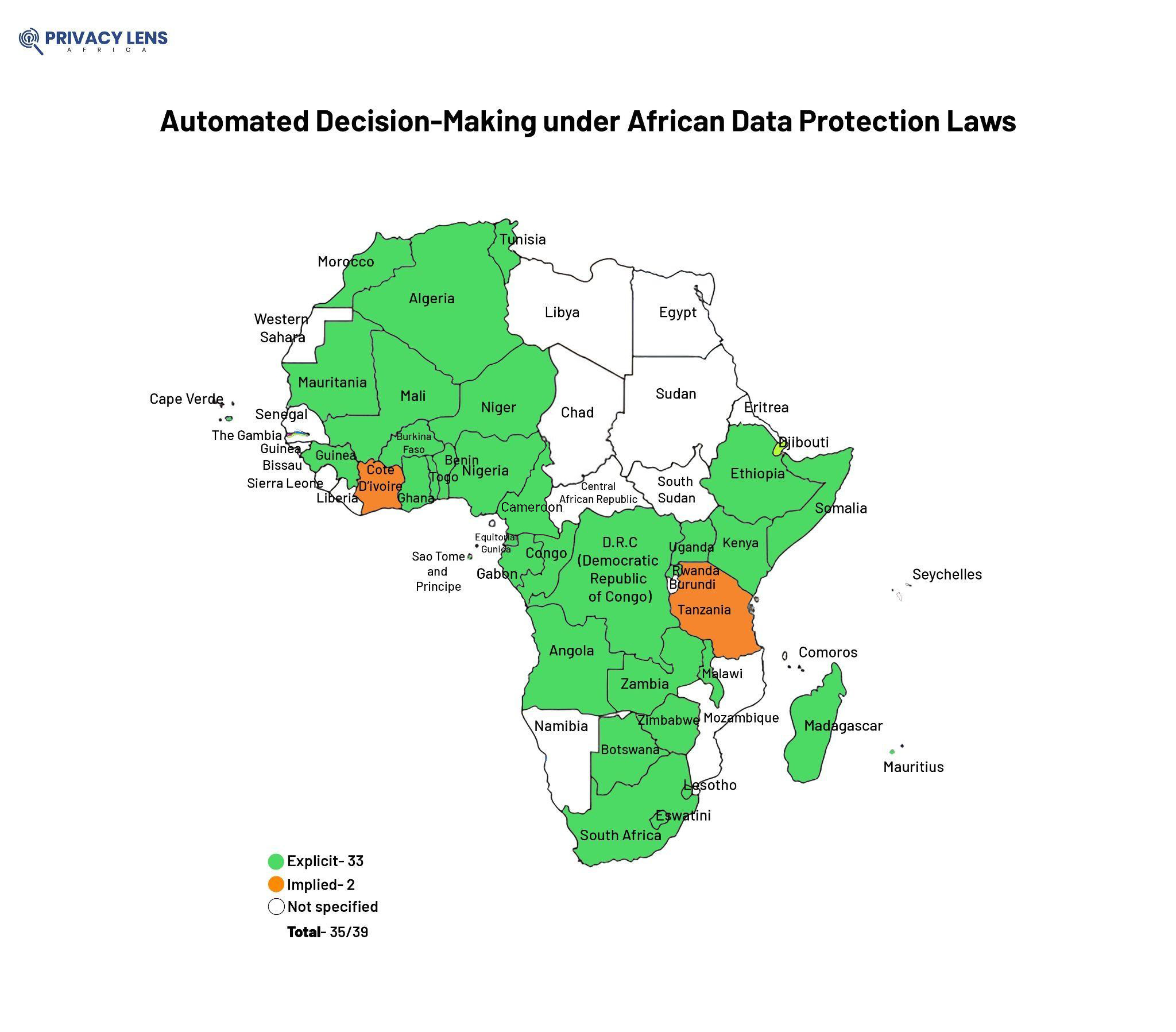

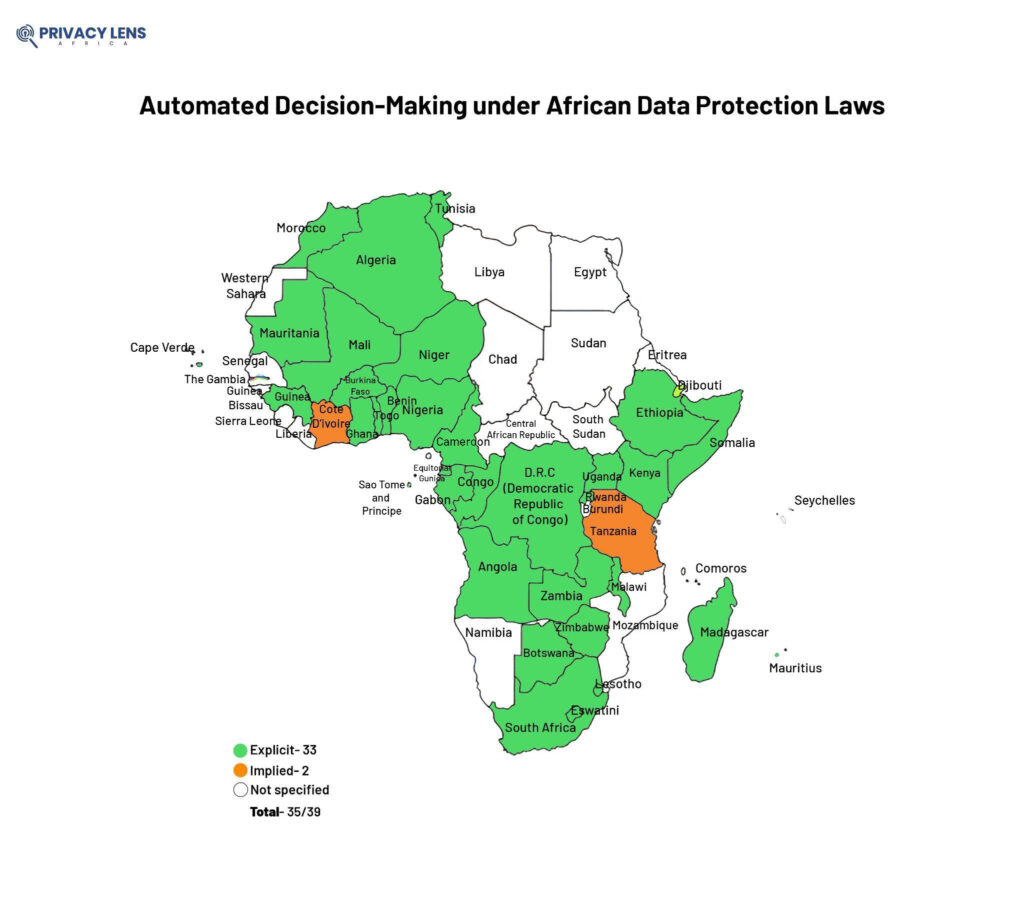

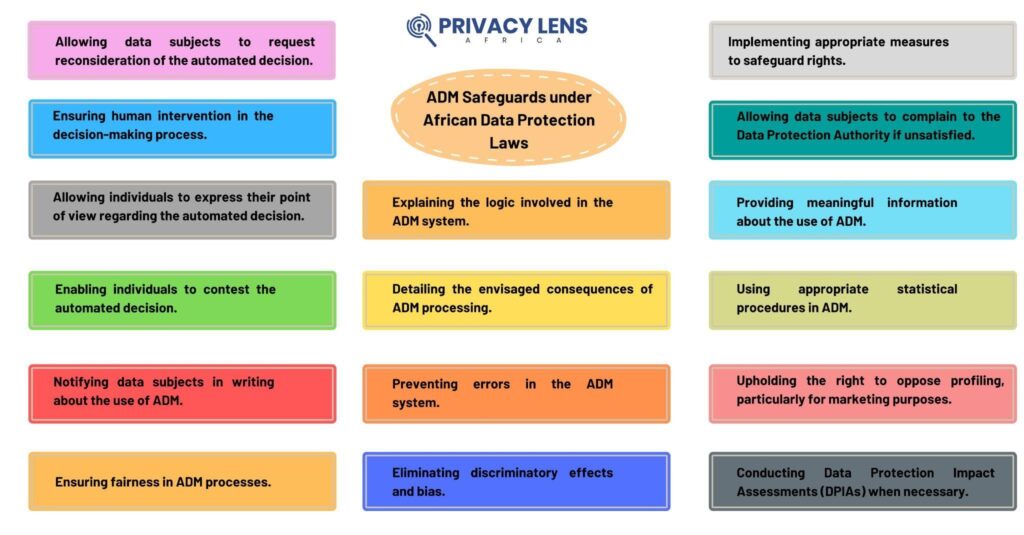

Of the 40 African countries with data protection laws, 36 recognise explicitly or implicitly the right of individuals not to be subject to solely automated decisions that have legal or similarly significant effects. This often includes the right to human intervention, an explanation of the decision, and the ability to contest the outcome. However, this right is often one of the most difficult to implement and enforce, potentially leading to interpretations from some DPAs across the globe that view it as a prohibition rather than a right. However, with the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its widespread applications across the continent, from facial recognition at airports for security, digital lending to assess creditworthiness to human resources to filter job applications and fraud detection, ADM is gaining prominence, making it crucial to understand its legal implications.

Understanding ADM: A Continent-Wide Perspective

Many African data protection laws have similar definitions for ADM. Kenya[1] and Nigeria,[2] for example, define it as “a decision based solely on automated processing by automated means, without any human involvement”. This definition highlights the key element of ADM: the absence of meaningful human intervention in the decision-making process, which can potentially lead to biased or discriminatory outcomes if not carefully managed.

However, there are nuances in how this concept is articulated. Mauritius, for instance, addresses ADM within the broader context of automated individual decision-making and profiling.[3] This approach acknowledges the close relationship between these two concepts, recognising that profiling often forms part of the ADM process.

Exceptions to the Rule: When is ADM Permitted?

While African data protection laws generally prohibit ADM that has legal or significant effects on individuals, they provide exceptions[1] for situations where ADM is necessary for entering into or performing a contract, such as automated fraud detection in online transactions. ADM is also allowed where specific legislation mandates it, for example, in national security or law enforcement contexts. Furthermore, ADM is permitted with the individual’s explicit and informed consent to the processing. While explicit and informed consent generally allows for ADM across many laws in the continent, Eswatini presents a unique exception. Instead of consent, Eswatini’s data protection law permits ADM when the processing is governed by a body of scientific or empirical evidence,[2] highlighting a distinct approach to balancing individual rights with technological advancements. Additionally, Cameroon[3] and Zimbabwe[4] only allows ADM under consent and legal obligation,[5]

In Rwanda, where ADM will involve using sensitive personal data, it is mandatory to do so under one of the conditions for processing sensitive personal data.[9] However, some laws limit the conditions; in Zambia, sensitive personal data can only be processed for ADM where there is explicit consent, public interest, and legal obligation.[10]

Safeguards

Recognising the potential risks of ADM, African data protection laws mandate various safeguards and measures to protect individuals’ rights. While some are generic, like Malawi, which expects controllers to “implement appropriate measures to safeguard the rights and freedom of the data subject”,[12] some laws are specific about the safeguards. These safeguards often include the right to obtain human intervention in the decision-making process, ensuring a human reviews the automated decision.[13] Individuals also have the right to express their point of view[14] and contest the automated decision.[15] Furthermore, data controllers must provide meaningful information about the use of ADM,[16] the logic involved in the ADM system and the envisaged consequences of the processing. In addition, some laws set specific time frames for the notification obligation. In Uganda, the data controller is expected to notify the data subject in writing of the use of ADM as soon as reasonably practicable. The data subject can ask the controller to reconsider the decision within 21 days,[17] and when unsatisfied, it can complain to the DPA within 14 days.[18]

Beyond the safeguards highlighted above, Kenya provides a comprehensive example outlining detailed requirements for data controllers engaging in ADM.[19] The regulation also mandates ensuring fairness, preventing errors, using appropriate statistical procedures, and eliminating discriminatory effects and bias. It further requires data controllers to uphold the right to oppose profiling (especially for marketing) and conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments when necessary. When ADM has legal or significant effects, it is considered high-risk processing, often triggering the need for a DPIA to assess and mitigate potential risks. However, while a country like Seychelles does not have this provision as a right, it included it as one of the triggers for conducting a data protection impact assessment.[20]

Conclusion

The right not to be subject to solely automated decision-making is a crucial aspect of data protection in Africa. While the legal frameworks across the continent share common ground in recognising this right, they also display nuances in their definitions, exceptions, and safeguards. As AI continues to evolve and ADM systems become more prevalent, African countries must ensure their data protection laws remain robust and adaptable to protect individuals from potential harm while fostering responsible innovation.

Version: Last updated February 28, 2025

- Section 22 of Kenya Data Protection (General) Regulation

- Section 65 of Nigeria Data Protection Act

- Section 38 of Mauritius Data Protecction Act

- Article 21 of Rwanda Privacy and Data Protection Law, Section 62(2) of Zambia Data Protection Act

- Section 45(2)(c) of Eswatini Data Protection Act

- Article 44(2) Cameroon’s Personal Data Protection Law

- Section 71(2) of South Africa Protection of Personal Information Act

- Section 27 (4) Uganda Data Protection and Privacy Act

- Ibid Section 27(3)

- Article 21 of Rwanda Privacy and Data Protection Law

- Section 62(4) of Zambia Data Protecction Act

- Section 25(3) of Malawi Data Protection Act

- Section 37(3)(a) of Nigeria Data Protection Act

- Section 37 (3)(b) of Nigeria Data Protection Act, Section 62(3) Zambia Data Protection Act, Section 71(3)(a) of South Africa Protection of Personal Information Act

- Section 37(3)(c) of Nigeria Data Protection Act

- Article 42(7) of Rwanda Privacy and Data Protection Law, Section 27(2) Uganda Data Protection and Privacy Act, Article 7.1 of Somalia Data Protection Act Guidance, Section 71(3)(b) of South Africa Protection of Personal Information Act

- Section 27(2)(b) Uganda Data Protection Act

- Section 27(5) Uganda Data Protection Act

- Section 22(2) of Kenya Data Protection (General) Regulation[1] Section 40(2)(a) Seychelles Data Protection Act