By Dorcas Tsebee

Different laws across many African countries require data controllers and processors to keep a detailed Record of Processing Activities (RoPA) to demonstrate adherence to the data protection principle of accountability. A RoPA is a comprehensive document that details how an organisation processes personal data. It is a critical tool for demonstrating accountability and compliance with data protection laws for both data controllers and processors. This documentation is vital for an organisation’s efforts to comply with data protection laws, offering insight into the purpose, means and related aspects of personal data processing.

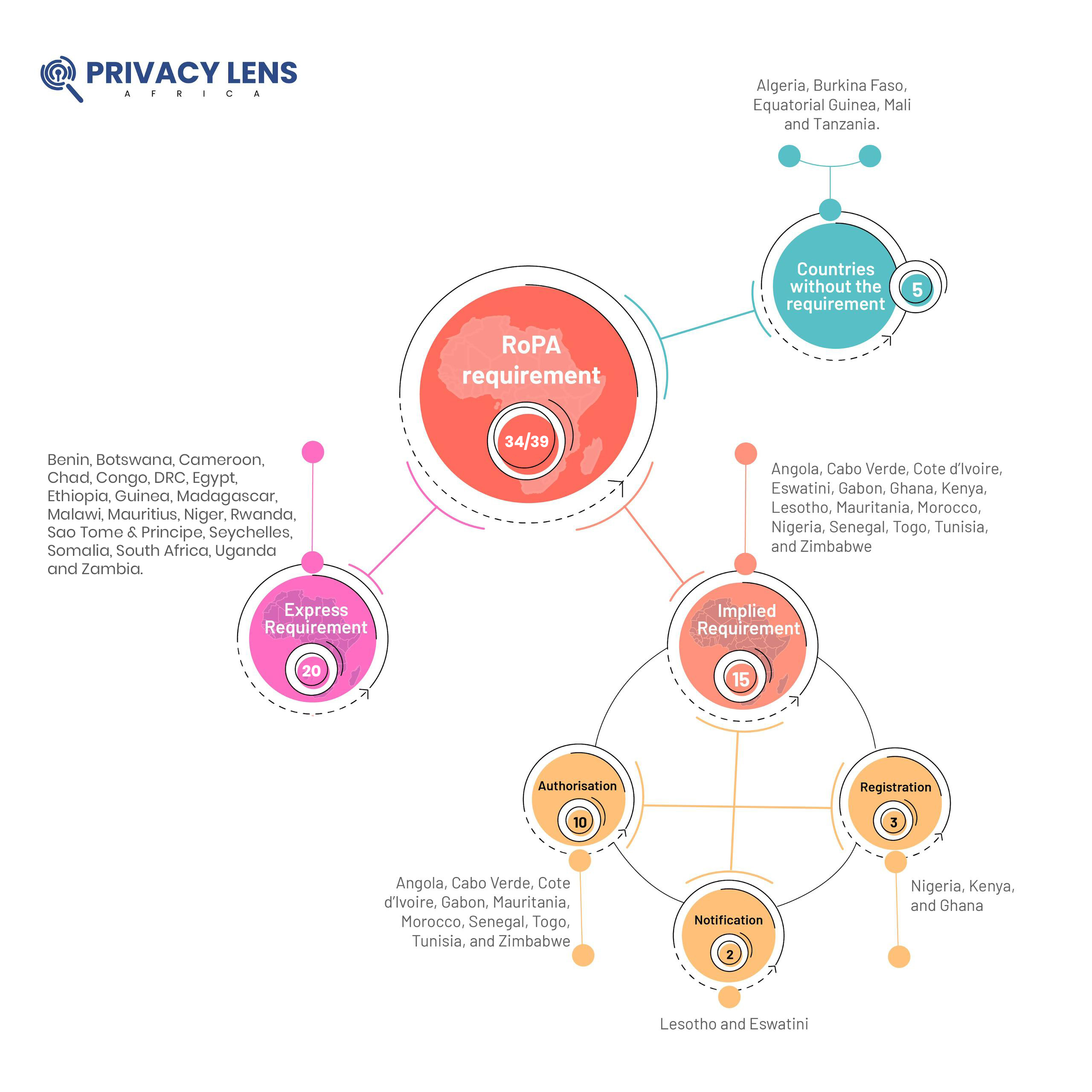

Of the 40 African countries with data protection laws, 20 explicitly mandate the maintenance of a RoPA, while 15 others implicitly provide for it in their authorisation, notification and registration requirements, bringing the total to 35 countries with RoPA requirements.

This means that only five1 countries are without this requirement.

Contents of a RoPA

RoPA and its Many Faces

The description of a RoPA varies across different data protection laws, with some referring to it as a “record” and others as a “register” or “list.” Additionally, the obligation to document RoPA under these laws differs; under some, it is embedded within other statutory requirements like applications for authorisation, permissions, declarations, opinions, notification, or registration processes. However, some laws expressly mandate data controllers or processors to maintain a RoPA, typically under the provision of the law detailing their responsibilities or obligations.

The content of a RoPA also differs by jurisdiction. In some countries where the laws place emphasis on obtaining authorisation for data processing, the information included in requests for such authorisations may go beyond what is traditionally expected in a RoPA. Despite these variations, the underlying principle remains the same: these documents are meant to detail the intended processing activities of data controllers, aligning with the essence of this discussion.

Therefore, in discussing the obligation to maintain a RoPA under African data protection laws, this article acknowledges the diversity in legislative requirements and perspectives, reflecting the multifaceted approach to data protection across the continent.

Documenting Processing Activities: Express Requirement

Some data protection laws explicitly require data controllers and processors to document data processing activities, and this could take the form of the descriptions noted above. For instance, the Mauritius Data Protection Act stipulates a clear obligation to maintain a detailed record of processing operations. Similarly, the Data Protection and Privacy Act of Rwanda mandates that data controllers and data processors keep a comprehensive record of all activities related to the processing of personal data. Malawi’s Data Protection Act also mandates that data controllers and processors maintain a record of each processing activity in writing. Ethiopia’s recently published Data Protection Act mandates the maintenance of a RoPA by data controllers. Notably, in these examples, the specifications of what must be included in these records vary; for instance, Rwanda’s legislation does not require information regarding security measures or the legal basis for processing activities, although the guidance on personal data inventory and readiness assessment checklist published in May 2023 contains the lawful basis for processing. This underscores the varying legislative requirements across countries.

The amended Seychelles Data Protection Act offers the most thorough provisions on what a RoPA should contain. It includes all previously mentioned aspects and extends to details on profiling, showcasing a more comprehensive approach to data processing documentation. It also includes a lawful basis for processing its content, which is omitted under some laws. However, as a matter of best practice, many organisations include a lawful basis for processing in their RoPAs.

In Zambia, the Data Protection Act also requires the maintenance of a RoPA, although it leaves the specifics of what this record should contain undefined, offering flexibility but potentially less guidance for entities on what to include. Similarly, South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) provides for the obligation to document processing operations, as specified under the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA).

Also, some laws have described this document as a register, typically documenting the activities of data controllers and processors. For example, Benin’s Digital Code requires the maintenance of a “register” of processing activities, detailing the minimum required information for both data controllers and processors. Notably, the processor’s register in Benin, like in some other countries, is tailored to the processing undertaken on behalf of each data controller. Benin and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) provide exemptions for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from keeping a RoPA unless their processing operations are deemed to pose risks to the rights and freedoms of data subjects, among other conditions. This significantly reduces the cost and eases the compliance burden for small-sized businesses.

Some data protection laws provide for the obligation to maintain a RoPA under the duties of data protection officers (DPO), representatives, or correspondents. In Guinea and Niger, the data protection correspondent (an equivalent of the DPO) is required to keep a list of all processing carried out on behalf of the controller. Similarly, Chad’s law provides that the DPO shall keep a record of the processing operations carried out by the controller, containing the information specified in Article 70. This information is submitted to the Data Protection Authority (DPA) before processing personal data to fulfil the notification obligations. Uganda also provides that one of the duties of a DPO is to keep a record of processing activities. It does not specify the contents of these records.

Other countries explicitly demanding RoPA compliance alongside other obligations like authorisation include Congo, and the DRC, where the laws provide a distinct obligation for controllers to keep a record of their processing activities and also submit an application for authorisation. Egypt also provides for the obligation to “maintain a record of personal data” by data controllers and data processors and also requires them to obtain a permit or licence to process personal data. In Botswana, the data protection representative is required to maintain a register of processing conducted on behalf of the controller. A notable addition to the main contents of a RoPA under Botswana’s law is a description allowing a preliminary assessment of the appropriateness of the security measures adopted by the controller or processor. The significance of this requirement is amplified by the fact that the register must be submitted to the Commissioner as part of an authorisation process, ensuring that the data protection practices are not just documented but also scrutinised for their adequacy in safeguarding personal data.

Further, some laws mandate the maintenance of a RoPA in order to fulfil the audit requirements. Somalia’s law presents a good example, as the law mandates data controllers and processors to maintain data processing records, building on the requirement to conduct a detailed audit of its data protection practices.

Some laws merge the responsibilities of maintaining a RoPA and declaring processing activities into a single provision, suggesting that fulfilling either obligation may suffice. Specifically, Madagascar’s law introduces the ‘principle of declaration or keeping a processing register’. It also specifies the information that must be submitted when requesting authorisation. Also, Sao Tome and Principe’s data protection law provides that the applications for authorisation and the records of processing of personal data must indicate the specified processing information.

Documenting Processing Activities: Implied Requirement

In some countries, the data protection law does not specifically require a RoPA, but it impliedly provides for this requirement through other obligations like obtaining authorisation, notifying the Data Protection Authority (DPA) or registering with the DPA as a controller or processor. These obligations involve submitting detailed descriptions of the organisation’s proposed processing activities. The information in these authorisation, notification or registration applications often aligns closely with what would be included in a RoPA, though it may include additional details. The information required generally covers:

- Identity and address of the data controller or duly authorised representative;

- Types of personal data to be processed;

- Categories of data subjects involved;

- Nature of processing operations;

- Purposes of processing;

- Data sharing and transfer arrangements;

- Security measures implemented to protect the data;

- Retention period of the processed information;

- Interconnections with other data processes;

- Authorised recipients of the data;

- Departments with access to the data;

- Process of exercising the right of access and rectification; and

- Involvement of any subcontractors.

The obligation to maintain these records and to communicate any modifications to the DPAs is a critical aspect of the authorisation, registration and notification processes in African data protection laws where they exist. These requirements implicitly incorporate the necessity of a RoPA, as the information needed for authorisation and notification often overlaps with the details that a RoPA would include. Interestingly, some jurisdictions go a step further by explicitly requiring the submission of a record of personal data processing as part of the authorisation process. Angola presents a notable example of this approach. The Angolan law mandates that data controllers provide “mandatory information” that includes comprehensive processing details similar to those found in a RoPA.

The countries with these authorisation requirements include Cabo Verde, Cote d’Ivoire , Gabon, Mauritania, Morocco, Senegal, Togo, Tunisia, and Zimbabwe. These countries mandate the submission of the processing information in the request for authorisation. While Chad, Congo, and the DRC contain authorisation requirements, the laws also expressly specify the obligation to maintain a RoPA.

The laws that provide for the registration obligation also require the submission of a list of processing activities. For instance, in Nigeria, Kenya, and Ghana, the Data Protection Acts require submitting documents or providing information during the registration process that replicates the contents of a RoPA.

Some countries integrate the registration and notification obligations. This is found in Eswatini, which imposes an obligation on data controllers to notify the DPA of the processing of personal information. The data controllers are required to inform the Authority about their personal data processing activities, with the content of this notification mirroring the information typically included in a RoPA. Moreover, the country’s registration regulation explicitly links the completion of these notification obligations to the process of registration under the Act. Essentially, fulfilling the registration requirement equates to notification but not the reverse. This is accomplished by providing the same type of information that a RoPA would require, such as the lawful basis for processing and the data retention periods.

Similarly, Lesotho’s Data Protection Act also provides for the notification of data processing by providing certain information, including the information contained in the RoPA, with the exclusion of retention periods and a lawful basis.

Beyond Record Keeping: The Role of DPAs in RoPA Management

Some laws extend the obligation to maintain a register of processing activities beyond data controllers and processors. For instance, Botswana’s data protection law obligates the data protection representative, commonly known as the DPO, to maintain a record of processing operations. Additionally, this law requires the Data Protection Commissioner to keep a register of these operations as reported by the DPO. This ensures that there is a centralised repository of processing activities, enhancing transparency and regulatory oversight. Chad’s data protection law takes a similar approach by requiring its Data Protection Authority (ANSICE) to keep a register of the processing operations that data controllers have submitted. This register is intended for public access, further promoting transparency and allowing individuals to be more informed about how their personal data is processed.

Some laws extend the obligation to maintain a register of processing activities beyond data controllers and processors. For instance, Botswana’s data protection law obligates the data protection representative, commonly known as the DPO, to maintain a record of processing operations. Additionally, this law requires the Data Protection Commissioner to keep a register of these operations as reported by the DPO. This ensures that there is a centralised repository of processing activities, enhancing transparency and regulatory oversight. Chad’s data protection law takes a similar approach by requiring its Data Protection Authority (ANSICE) to keep a register of the processing operations that data controllers have submitted. This register is intended for public access, further promoting transparency and allowing individuals to be more informed about how their personal data is processed.

The involvement of DPAs in overseeing the maintenance and, in some cases, public accessibility of RoPAs further emphasises the role of regulatory bodies in ensuring data protection compliance.

Conclusion

The obligation to maintain a RoPA under the 34 African data protection laws reflects the important role it plays in ensuring compliance with the data protection principle of accountability across the continent. The RoPA is a critical tool for accountability and transparency, detailing organisations’ processing of personal data, methods, purposes, sources and safeguards. It helps in checking an organisation’s data management practices and fulfilling other obligations under the data protection laws, like effectively managing data subject rights. As African data protection laws evolve, RoPA remains a crucial aspect of data protection, and more countries will incorporate the requirement into their laws.

Version: Last updated February 28, 2025.

- Algeria, Burkina Faso, Equatorial Guinea, Mali, and Tanzania.

- Section 33 Mauritius DPA

- Article 17 Rwanda’s Data Protection and Privacy Act

- Malawi’s Data Protection Act, Section 29.

- Ethiopia’s Data Protection Proclamation 2024, Article 46.

- Seychelles Data Protection Act, Section 37

- Zambia’s Data Protection Act, Section 45

- Section 17 of POPIA.

- Benin’s Digital Code, Article 435

- DRC’s Digital Code, Article 228

- Article 14, Guinea Cybersecurity and Data Protection Law and Article 12, Niger’s Data Protection Law.

- Article 67, Chad’s Data Protection Law.

- Section 47(3)(c) of Uganda’s Data Protection and Privacy Regulations.

- Congo’s Data Protection Law, Article 68

- DRC’s Digital Code, Article 230

- Article 4(9) under the broad obligations ascribed to data controllers

- Article 5(9) includes other details such as details of processor’s Data Protection Officer, the period, restrictions, and scope of processing, the mechanisms for deleting or modifying the personal data.

- Section 37 of Botswana’s Data Protection Act.

- Somalia DPA Guidance Art. 7.3 and DPA Art. 19.

- Article 43 & 47 Madagascar DPA

- Ibid Article 49.

- Article 24, Sao Tome & Principe Data Protection Law.

- Article 32 and Section 57, respectively.

- Angola’s Data Protection Law, Article 37(1).

- Cape Verde’s Data Protection Law, Article 25 & 26.

- Article 9, Cote d’Ivoire DPA

- Article 58 of Gabon’s law.

- Section 43 of Mauritania’s Data Protection Act.

- Article 15 of Morocco’s Data Protection Law.

- Article 22 of Senegal’s Data Protection Law.

- Article 10 of Togo’s Data Protection Law.

- Article 8 of Tunisia’s Data Protection Law.

- Section 21 of Zimbabwe’s Data Protection Act.

- Chad’s Data Protection Law, Article 70.

- Article 43 of Congo’s Law. Congo is one of the laws with distinct provisions on RoPA and authorisation.

- Article 188 of the DRC’s Digital Code. There is also a distinct provision of RoPAs.

- Section 44 of the Nigeria Data Protection Act 2023, Section 27 of Ghana’s Data Protection Act 2012, and Section 19 Kenya’s Data Protection Act.

- Section 46(2) of the Eswatini Data Protection Act.

- Section 53(2) of Lesotho’s Data Protection Act.

- Section 37, Botswana DPA.

- Chad’s Data Protection Law, Article 74.

- Algeria, Burkina Faso, Equatorial Guinea, Mali, and Tanzania [↩]