By Dorcas Tsebee and Ridwan Oloyede

One of the key accountability mechanisms under data protection laws is the requirement to conduct a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) where data processing activity is likely to result in high risk to the rights and freedoms of a data subject. A DPIA serves as an important risk management tool that helps identify potential data protection risks before a new processing activity (such as the launch of a new technology, product, project, or service) and develop measures to mitigate the risks. Conducting a DPIA also feeds into embedding data protection by design into the development of new technologies, products, and services.

The requirement to conduct a DPIA is found under some data protection laws in Africa. Under these laws, ‘high-risk processing’, which requires a DPIA, includes the use of an automated processing system, the processing of sensitive personal data, the systematic monitoring of a publicly accessible area on a large scale, or similar processing that poses risks to a data subject. They sometimes also prescribe the requirements, which may include the documentation of the envisaged processing and its purpose, the necessity and proportionality of processing in relation to purpose, the assessment of the risks to the rights and freedoms of a data subject, and the measures envisaged to address the risks.

DPIA: The Many-Named Guardian of Risk

The definition of a DPIA is similar across these laws, although with slight variation in the choice of name. While the name differs, the meaning and purpose remain largely the same. While most of the countries that provide for it refer to it as “Data Protection Impact Assessment,” some countries opt for “Data Privacy Impact Assessment,”[1] “Impact Analysis,”[2] or “Personal Information Impact Assessment.”[3]

The Different Mosaics of DPIA in Africa: A Panorama of Convergence and Divergence

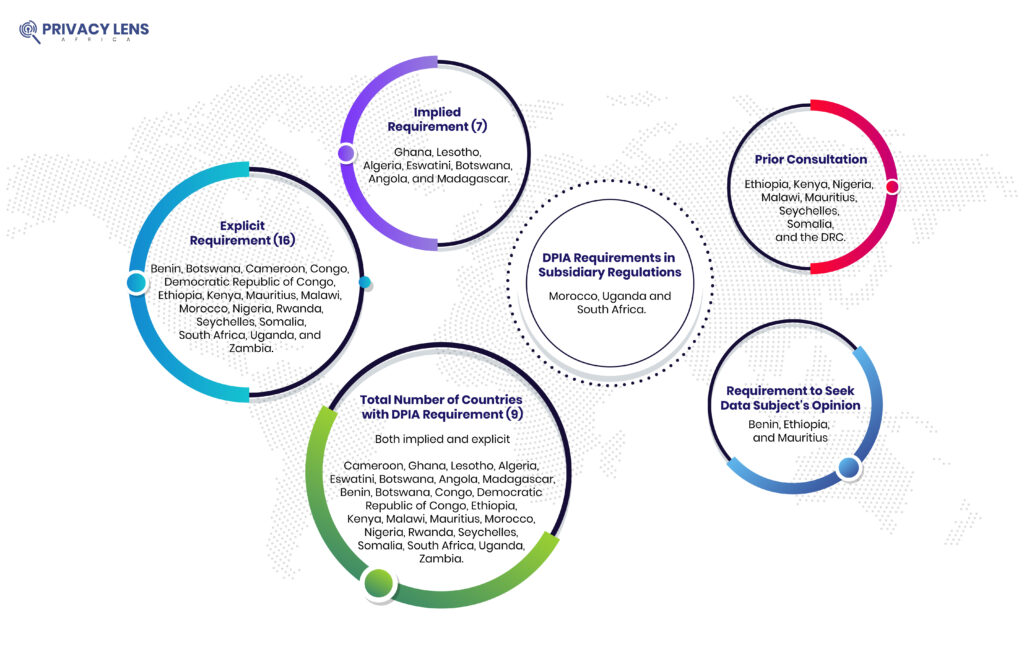

The requirement to conduct a DPIA is present in some data protection laws, although with slight variations. However, there is convergence across these countries on the categories of processing that may require a DPIA. Some of the provisions of the DPIA laws are explicit, while others are implied. While some countries specifically make it a requirement, others do not provide for DPIA in their substantive laws but have made regulations and additional instruments that expressly provide for it. For example, the primary data protection law in Morocco does not contain any provision on DPIA, but the Moroccan Authority’s Deliberation No. D-188-2020 of December 14, 2020, introduced DPIA.[4] Similarly, Uganda’s substantive data protection law does not explicitly provide for a DPIA, but the Regulations that were issued in 2021 expressly provide for it.[5] A similar situation exists in South Africa, although it is made part of the obligations of information officers.[6]

Out of the 40 African countries with data protection laws, 17 of them have explicit DPIA requirements

However, each of the laws has a unique way of introducing it into their laws, although the meaning, contents, and when it is required remain the same across the countries. Depending on the structure of each law, some include the requirement for conducting a DPIA as part of the obligations and duties of data controllers and processors,[9] while others provide for it as part of the general data processing requirements.[10] In Côte d’Ivoire, although the DPIA requirement is not a provision in the substantive law, the supervisory authority (ARTCI) requires it as a good practice for processing sensitive personal data.[11] For the countries with implied DPIA requirements, most of the provisions are based on the general obligation of data controllers to implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to protect personal data. In addition, the implied DPIA provisions mandate data controllers to identify risks to personal data they process, establish appropriate safeguards, verify the effectiveness of the safeguards, and regularly update existing measures.[12]

Another noticeable trend is prior consultation with the data protection authority as a condition for continuing a processing activity after a DPIA has been conducted under some of these laws. For example, Kenya’s Data Protection Act provides that the impact assessment report shall be submitted to the data protection authority (ODPC) 60 days before data processing. In Nigeria, consultation with the data protection authority is also required before processing, where the DPIA discloses a high risk to the rights and freedoms of a data subject.[13] In Mauritius, prior consultation with the data protection authority is also a requirement, and the data controller or processor may be required to provide the DPIA for assessment.[14] For context, in its 2022 report, the Mauritius Data Protection Commission disclosed that it analysed four DPIAs within the year.[15] The DRC also mandates consultation where a DPIA discloses a high risk if the data controller does not take measures to mitigate the risk.[16] In Benin and Congo, although the data controller is not required to consult with the supervisory authority when carrying out an impact analysis, they are required to seek advice from the data protection officer if one has been appointed. The requirement is also available under the laws in Ethiopia[17] and Seychelles.[18]In addition, in Malawi and Somalia, the DPIA report must be submitted to the DPA before commencing processing.[19] The trend shows the role of the data protection authority in mitigating risk. The implication is that for processing activities that may involve high risks to data subjects and where the risk cannot be mitigated, the data protection authority can advise on how to further mitigate the risk or stop such processing.

The provisions on DPIA under the various laws list certain processing activities that require a DPIA.[20] Some of these laws mandate that data protection authorities publish a list of processing activities that may require a DPIA.[21] For example, Nigeria’s data protection law provides for the requirement of a DPIA but states that the data protection authority will issue regulations on the categories of processing and the persons subject to the requirement for conducting a DPIA.[22] The requirement to publish a list of processing operations that require a DPIA is also found in Benin, Uganda, and Zambia.[24] In addition, some laws require data controllers and processors to seek the views of data subjects on whether the intended processing is appropriate.[25] This is likened to a consultation with the data subjects before a processing activity. In Benin, the data controller may also seek the opinion of the concerned data subject where it is appropriate.[26] In addition, it is a requirement in Benin to conduct a post-DPIA analysis to ensure that the processing is carried out under the DPIA.[27]

In conclusion, the requirement to conduct a DPIA is increasingly becoming part of modern data protection laws (noticeable in the DRC, Kenya, and Nigeria, among others) and amendments to older laws on the continent (Benin and Mauritius, among others).

Version: Last updated February 28, 2025.

[1] Nigeria. The Data Protection Implementation Framework called it “Data Protection Impact Assessment.”

[2] Benin, Congo, DRC, and Morocco.

[3] South Africa.

[4] Deliberation No. D-188-2020 dated 14/12/2020 governing the Impact Assessment relating to

data protection (DPIA) https://www.cndp.ma/images/deliberations/CNDP_Deliberation_AIPD-D-188-2020-_2020-12-14.pdf.

[5] Section 20(2) of the 2019 Act and Regulation 12 of the 2021 Regulations.

[6] Regulation 4 of the POPIA Regulations 2018.

[7]Benin, Botswana, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mauritius, Malawi, Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia.

[8] Ghana, Lesotho, Algeria, Eswatini, Botswana, Angola, and Madagascar. See Iheanyi Nwankwo and Nelson Otieno, ‘Adopting Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)’ ( 2022: Institute for Legal Informatics, Leibniz Universität, Germany).

[9] Rwanda DPA, Article 8.

[10] For example, Nigeria and Kenya.

[11]Nwankwo and Otieno (n 9)

[12] Lesotho DPA, Section 20(2), and Eswatini DPA, Section 14(2).

[13] Section 28(2).

[14] Section 35 Mauritius Data Protection Act.

[15] https://dataprotection.govmu.org/Documents/AR22%20DPO.pdf

[16] DRC Digital Code, Article 246.

[17] Section 48

[18] Section 41

[19] Section 30 (4) Malawi and Article 29(1)(b) Somalia.

[20]Benin, Congo, Rwanda, South Africa, and Zambia.

[21] Zambia, Uganda, and Benin.

[22] Section 28(3).

[23] Regulation 4.2. However, the NDPA has filled that gap by providing for the contents of a DPIA.

[24] Article 428, Regulation 12(3) and Section 46(3), respectively.

[25] Mauritius DPA, Section 34(4).

[26] Article 428.

[27]Also available in Zambia.